By Vaishnavi Vaidya, Allison Gibson, and Jennifer Kolker | October 4, 2021

As part of our efforts to track health inequities exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and what cities are doing to combat these inequities, we are engaged in a qualitative analysis of 14 BCHC cities (chosen based on data availability, size, and location). This analysis consists of 1) systematic coding of city’s publicly available policies and initiatives to address inequity in testing and vaccination 2) qualitative interviews with senior health department officials and 3) a second round of systematic coding to capture changes in strategy and policy since the first round of coding. Below are our findings from the first part of our qualitative analysis.

COVID-19 testing, and vaccination equity was assessed in the following 14 cities:

Baltimore, Chicago, Detroit, Houston, Indianapolis, Las Vegas, Minneapolis, New York City, Philadelphia, Portland, San Diego, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Long Beach

Following a preliminary review of all 14 cities’ COVID-19 websites to inform topic areas and search terms, we developed a comprehensive coding guide that captured COVID-19 equity strategies across all 14 cities, focusing on the following key components:

The existence of formal COVID-19 equity plans detailing plans to ensure equity in testing and/or vaccination

Examples of key initiatives cities implemented to address inequity in COVID-19 testing and/or vaccination

Key partnerships for local health departments in their COVID-19 response

The goal of the qualitative review was to characterize the policies and practices occurring at the city level. Our research was conducted from March 5, 2021 to May 10, 2021.

Equity in COVID-19 Testing

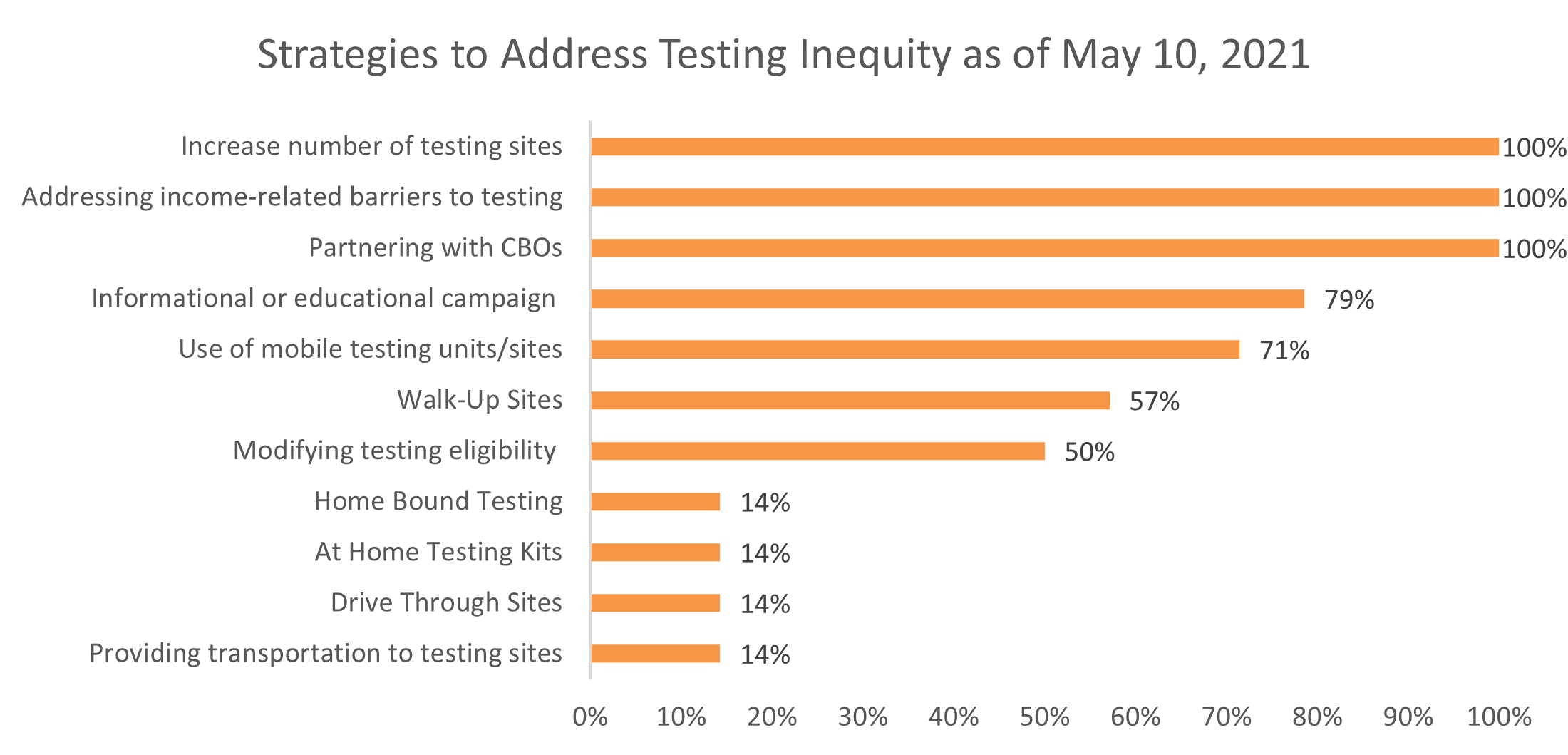

All 14 cities used 1) Partnerships with community organizations 2) Strategies for addressing income-related disparities (primarily by waiving the costs associated and not requiring insurance) and 3) Increasing testing sites in underserved areas. Additionally, 11 cities (79%) relied on 1) Informational or educational campaigns to encourage testing and 2) Other means, mainly offering walk-up testing sites. Mobile testing units or pop-up sites were also used by most cities (71%, n=10).

While most cities created publicly available equity plans surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic, only six of them (43%) included explicit reference to equitable testing. Regardless of whether or not they had publicly available plans, all 14 cities employed equity strategies to approach testing.

To increase testing, cities relied mostly on cross-sector partnerships, cost reduction methods, and increased access to testing sites. Partnerships, specifically those with community-based organizations (CBOs) and health care systems, helped to relieve the burden on local health departments and increase community trust and testing acceptance. The role of CBOs in partnership efforts is critical as these organizations are diversified across cities, embedded within communities, and often have pre-existing ties to the local community. Diversity in testing sites and testing staff meant greater options for people who may distrust the standard healthcare system or larger government healthcare efforts due to years of feeling marginalized and misled (Burns, 2020).

In the early weeks and months of the pandemic, the key strategy to contain the virus was through tried-and-true public health measures: testing, isolation, and quarantine. However, despite federal mandates (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2021) requiring free testing to everyone, many have been skeptical, assuming that there would be a cost associated to getting tested or with seeking treatment if a test were to be positive. To overcome this, all cities provided targeted and repetitive communications that free testing was available regardless of insurance status, with hope of incentivizing hesitant populations to get tested.

Equity in COVID-19 Vaccinations

As the pandemic surged, despite improvements in testing and treatment of the virus, the public health community widely agreed that vaccinating the majority of the public was the way out of the pandemic (Weise, 2021). Though the federal government focused its efforts on vaccine development through Operation Warp Speed, many questions remained surrounding the mechanics of vaccine allocation and distribution, through the fall of 2020 (Michaud & Kates, 2020). Limited vaccine supply in December of 2020, when vaccines first became approved for the general population, heavily restricted who was eligible to receive the vaccine. Guidelines for a phased roll-out of the vaccine prioritized those at highest risk for exposure, severe illness, and death. This led to great disparities in who received the vaccine early on. Even when vaccine supply increased and much of the adult population became eligible for the vaccine, long-standing systemic inequities led to disparities in who became vaccinated.

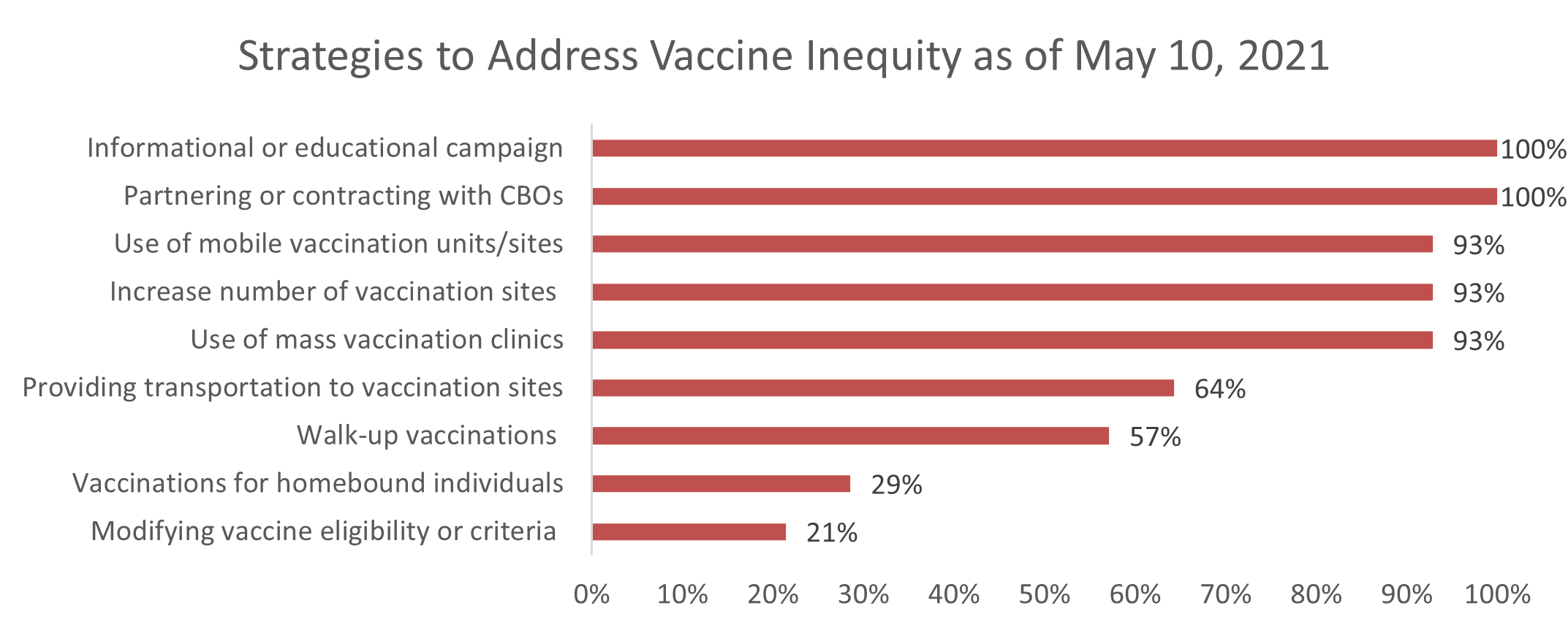

All 14 cities engaged in efforts to advance equity in COVID-19 vaccine distribution. The strategies used to address vaccine inequity focused on partnerships with community organizations to independently distribute vaccines (100%, n=14), informational campaigns to encourage vaccines focused on hard-to-reach populations (100%, n=14), increased numbers of sites (93%, n=13), and the use of mobile and pop-up vaccine units (93%, n=13). Universities and other academic institutions and health and hospital systems were the most common partner in vaccination efforts, though larger systems, they have the capacity to remove costs, increase sites, improve communications through diverse staff and education backgrounds, and provide mobile sites. The other main partners were those rooted in the community and best positioned to reach underserved populations. These were community-based organizations or non-profits and community clinics, often working in coordination with health systems or non-profits.

All 14 cities utilized mass vaccination clinics, often set up in convention centers and stadiums and often with federal support. Mass vaccination clinics were initially seen as the means of reaching the largest number of people in the fastest amount of time (Weise, 2021) . However, mass vaccine sites, which were commonly large sports stadiums or within city centers, were often located in areas that were inaccessible to communities with the highest COVID-19 case rates and lowest vaccination rates. Additionally, mass vaccination sites often were only open during normal work hours and had limited weekend slots making it difficult to utilize for those with inflexible work schedules (Lu, Gondi, & Martin, 2021).

Conclusion

These findings provide a preliminary understanding of how major cities in the U.S. have worked to address inequities in testing and vaccination through health department policy and practice. However, conducting an equity analysis of COVID-19 testing and vaccinations during an ongoing pandemic posed many challenges. As the pandemic is still ongoing and vaccine distribution was at its early stages during the time of this analysis, there were frequent changes to strategies, based on case rates, vaccine supply, and eligibility.

Interviews with key health department officials and further research on the progress and additional measures taken by cities will be used to supplement these findings and provide greater insight and understanding into the key mechanisms used to achieve equity.

References

Burns, S. (2020, December 18). Mayor Brandon M. Scott Announces Initiative to Mitigate Disproportionate Impact of COVID-19 on Latinx Community. Retrieved from City of Baltimore: https://mayor.baltimorecity.gov/news/press-releases/2020-12-18-mayor-brandon-m-scott-announces-initiative-mitigate-disproportionatete Disproportionate Impact of COVID-19 on Latinx Community

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2021, February 26). Biden Administration Strengthens Requirements that Plans and Issuers Cover COVID-19 Diagnostic Testing Without Cost Sharing and Ensures Providers are Reimbursed for Administering COVID-19 Vaccines to Uninsured. Retrieved from Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/biden-administration-strengthens-requirements-plans-and-issuers-cover-covid-19-diagnostic-testing

Lu, R., Gondi, S., & Martin, A. (2021, April 12). Inequity in vaccinations isn’t always about hesitancy, it’s about access. Retrieved from Association of American Medical Colleges: https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/inequity-vaccinations-isn-t-always-about-hesitancy-it-s-about-access

Michaud, J., & Kates, J. (2020, October 20). Distributing a COVID-19 Vaccine Across the U.S. - A Look at Key Issues. Retrieved from Kaiser Family Foundation: https://www.kff.org/report-section/distributing-a-covid-19-vaccine-across-the-u-s-a-look-at-key-issues-issue-brief/

Weise, E. (2021, January 28th). ‘This is fantastic’: Mass vaccination clinics to play key role in ending COVID-19 pandemic. Retrieved from USA Today: https://www.usatoday.com/in-depth/news/health/2021/01/28/mass-vaccination-clinics-play-key-role-ending-covid-pandemic/6699559002/

Citation

Vaidya, V., Gibson, A., Kolker, J. Equity in COVID-19 Testing and Vaccination: A Qualitative Analysis. Philadelphia, PA. Drexel University; Oct 2021.