By VAISHNAVI VAIDYA, ALINA SCHNAKE-MAHL, USAMA BILAL, JENNIFER KOLKER, RAN LI, EDWIN MCCULLEY | January 5, 2021

Since March, state and local governments have had to make challenging decisions to determine which services are essential, when to reopen certain sectors of the community, and to ensure that precautions are taken for the safety of their residents. These decisions have had to balance several aspects, including protecting public health and maintaining economy activity. With many food establishments forced to shutter or transition to takeout only service, the pandemic has led to widespread job loss and economic hardship in the restaurant industry. Following early restrictions on dining, state and local governments had to weigh these issues in decisions about reopening and—in recent months—shuttering again. A lack of federal guidance when making decisions about reopening indoor dining during the COVID-19 pandemic has created wide heterogeneity in the decisions made by local and state governments in terms of weighing more restrictive against looser policies. Often, local decisions on reopening and closing businesses have differed from the state’s guidelines, leading to conflicts between state and local governments.

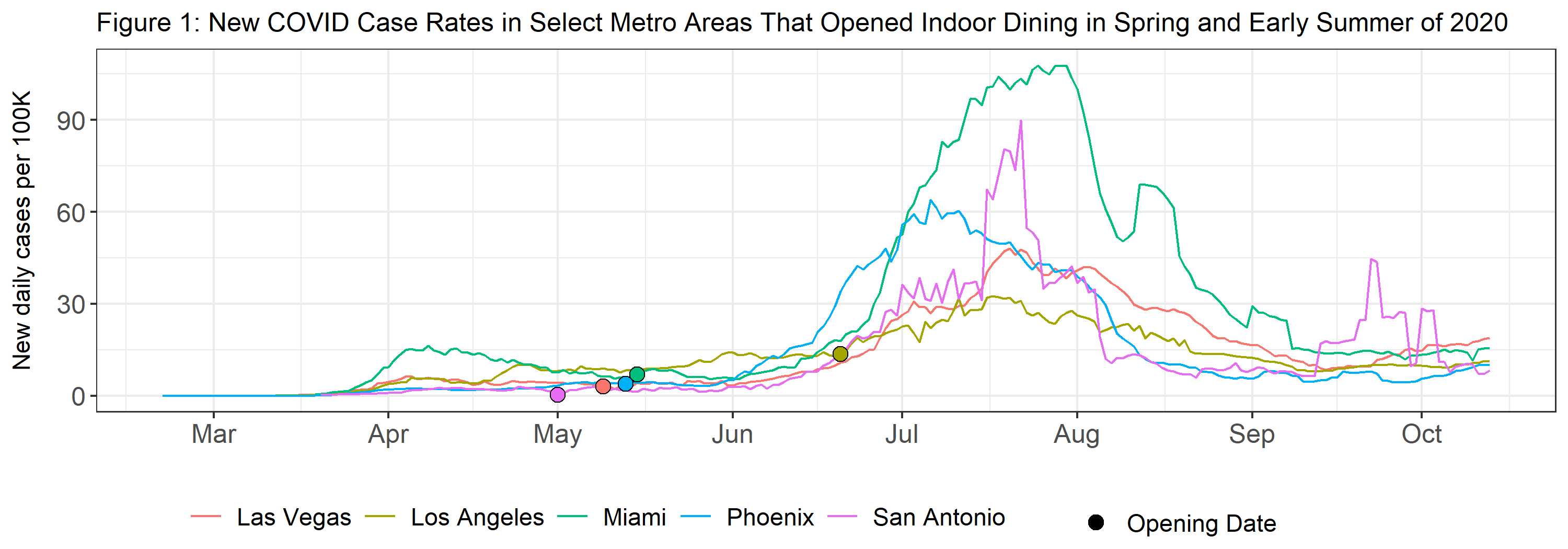

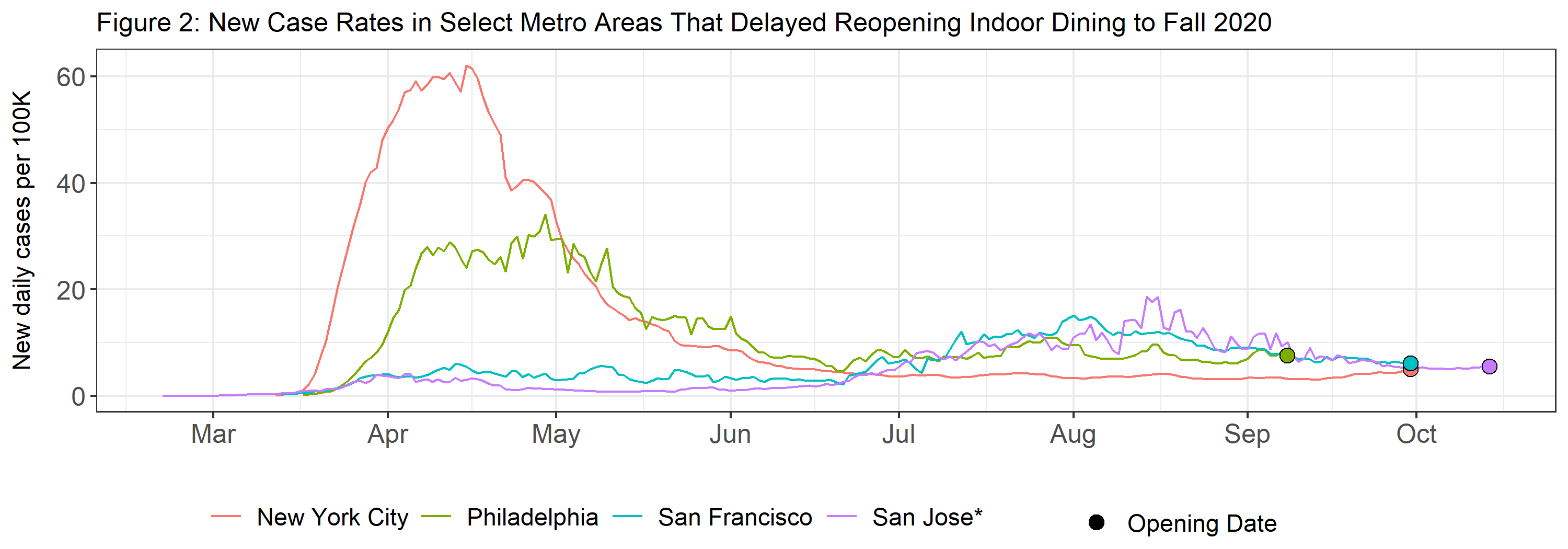

The conflicting power dynamics, as well as geographic differences in COVID-19 spread, resulted in substantial variation in the timing of reopening and closing across the country. Although most BCHC cities shut down indoor dining earlier in the spring of 2020, all BCHC cities reopened indoor dining in the summer and fall, with varying timelines. For example, cities in Texas opened indoor dining facilities on May 1st while cities like Chicago and Denver opened indoor dining in late May and June.1 Some cities like San Francisco, San Jose, Philadelphia, and New York City kept indoor dining closed until September and October, basing their decision to remain closed on more restrictive metrics for reopening.2 In some cities, such as those in Texas, state-level preemptive policies forced reopening of indoor dining sooner than what local officials would have wanted.3

Cities that reopened indoor dining in the spring and earlier in the summer (Figure 1) experienced surges in cases in the weeks after reopening, while cities that delayed reopening to later in the summer and into the fall (Figure 2), did not see similar increases through the summer. Decreases in case rates later on in the summer in cities that opened indoor dining earlier may be attributed to other restrictions and mitigation strategies. As the reopening of indoor dining appears to likely impact community transmission of COVID-19, continued monitoring of cases and positivity rates as well as the ability to quickly roll back reopening measures are essential in proceeding safely while responding to economic distress in the restaurant industry.

Once again, preemption at the state level has prevented cities, such as those in Texas, Arizona, Florida, and North Carolina, from implementing more restrictive COVID-19 policies at the local level, even after community transmission persisted.4 However, when possible, many cities have made reopening decisions informed by the specific characteristics of their jurisdictions including rates of community transmission and population size. For example, California set a minimum group of restrictions but allowed localities to enact stricter policies, also known as floor preemption.5

The experiences of BCHC cities reinforce the importance of moving through phases of reopening gradually with established procedures for rolling back reopening measures as needed with effective communication to the public. Remaining transparent with the public about what influences decisions on opening or closing businesses can clarify questions on why some cities choose to enact such policies. With record daily cases and no signs of the current upward trend in cases, hospitalizations, and deaths subsiding, local officials are faced with critical decisions to mitigate the spread of the virus. Closing of indoor dining during the winter months creates a tough situation for those in the restaurant industry. While this analysis suggests that delaying reopening of indoor dining to late summer or early fall may have played a role in mitigating the spread of COVID-19, further causal analysis is required to help estimate the impact of summer reopening and winter reclosing of indoor dining. Please refer to the UHC Policy Brief on Indoor Dining and COVID-19 for more details.

References

1 Fernández, “Texas Restaurants, Retailers and Other Businesses Can Reopen Friday. Here’s the Rules They Have to Follow.”; “Indoor Dining Can Return in Chicago on June 26, But With Restrictions, Mayor Announces – NBC Chicago”; Reedy, “Colorado Restaurants Can Reopen for Dine-In Service On May 27.”

2 “San Francisco Restaurant Dining Rooms Will Reopen on September 30 - Eater SF”; “Indoor Dining Returns to Santa Clara County — on a Sunny Day Made for Alfresco Meals”; “Indoor Dining Is Back on September 8 in Philadelphia | Department of Commerce”; “Governor Cuomo Announces Indoor Dining in New York City Allowed to Resume Beginning September 30 with 25 Percent Occupancy Limit.”

3 Platoff, “Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton Warns Austin, San Antonio, Dallas to Loosen Coronavirus Restrictions.”

4 “State Preemption and Local Responses in the Pandemic | ACS.”

5“San Francisco to Join Bay Area Counties to Preemptively Adopt California’s Regional Stay at Home Order in an Effort to Contain COVID-19 Surge | Office of the Mayor.”